Exhibition 01.10.2021 - 30.11.2021

The European Parliament's visitors' center Luxembourg Square, 100 - 1050 Brussels

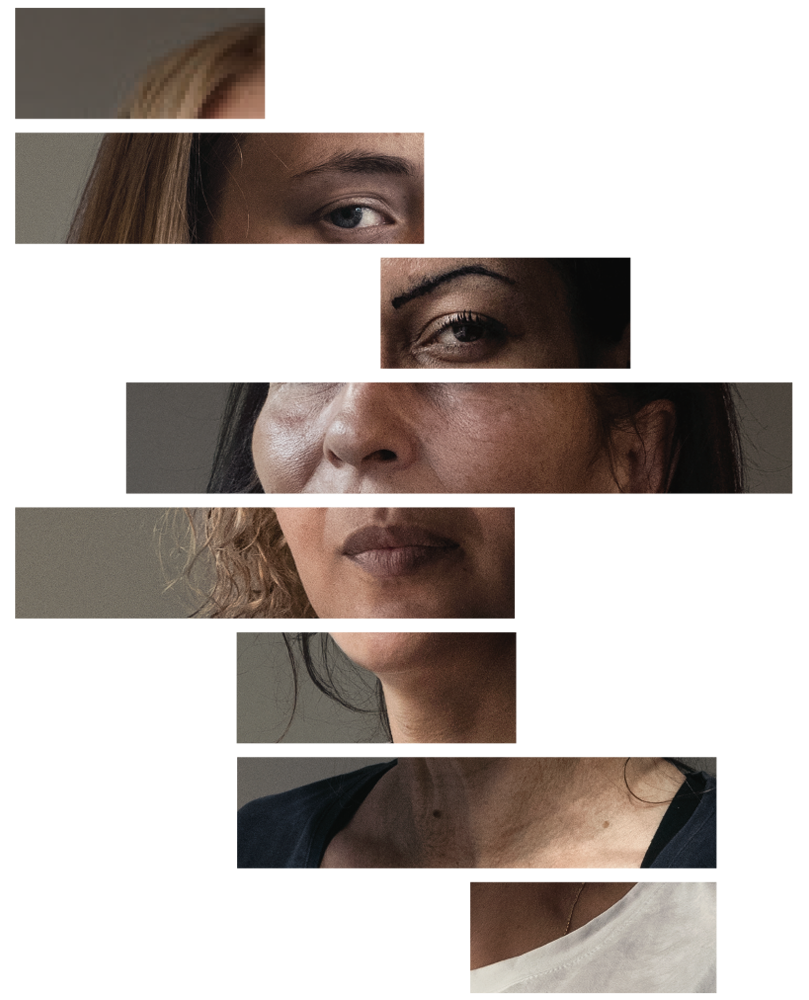

Portraits of women accompanied by the Samusocial of Brussels

Through the eyes of photographer Gaël Turine and texts written by Anne-Cécile. Huwart, the visitor is invited to discover the woman hidden behind each and every case of homelessness.

femmes

Exhibition 01.10.2021 - 30.11.2021

The European Parliament's visitors' center Luxembourg Square, 100 – 1050 Brussels

Portraits of women accompanied by the Samusocial of Brussels

Through the eyes of photographer Gaël Turine and texts written by Anne-Cécile Huwart, the visitor is invited to discover the woman hidden behind each and every case of homelessness.

You will discover the portraits of four women who agreed to have their image and their story shared with the general public.

These four testimonies are only an extract of a series of fifteen portraits that are fully displayed in an exhibition to be seen in the Parlamentarium, the European Parliament's visitors' center, from October 1 to November 30, 2021.

Each portrait presented here is accompanied by an audio sequence, an oral restitution by actress Charlotte de Metsenaere, of each of the testimonies given by the women our teams accompanied.

These are women who are ‘chronically homeless’, ‘on the streets’, ‘victims of violence’, ‘victims of human trafficking’, ‘sick’, ‘migrants’, ‘exiles”, ‘drug addicts’, ‘alcoholics’...

But they are, first and foremost, women.

Women with a life and a journey - often a traumatic one. But also, and most importantly, women with a future, a horizon on which it is still possible to act in a positive way.

In order for them to be (re)considered as women, accommodation facilities need to welcome them in a way that allows their residents to recover and rediscover their identities as women.

During the COVID-19 crisis, the Samusocial of Brussels has had the opportunity to open the ideal centre for women without shelter in the Helmut Kohl building, provided by the European Parliament in Brussels.

For four months, between May and August 2020, EU officials who were working remotely gave up their offices for 279 women. As a result, they had accommodation in human-sized rooms, day and night, without being forced to leave the centre every morning, without seeing their lives reduced every day to a bundle of belongings that reminds them, with a sense of painful inevitability, of their homelessness. 64 of these women have already been directed towards solutions that will take them off the streets.

Jennifer

ROOM 203

Listen

Jennifer

ROOM 203

‘My adoptive father raped me and got me pregnant. I was 15 when my daughter was born. I tried to get rid of the baby by throwing myself down a staircase, but it didn’t work.

I dropped out of school and left home. On the streets of Liège, the city where I grew up, I fell in with the wrong crowd. I started drinking and taking drugs. I met a man, and we had three kids together. I’ve known other men too; some were violent. One tried to hit my daughter…

I’ve been through a lot on the streets. In Brussels, I used to sleep in a tent close to Gare du Midi – before someone set fire to it.

Today my children are 24, 19, 17 and 15 years old. Despite all the horrible things that have happened, I am trying to rebuild my life. I keep going. I should be moving into a shelter; I don’t feel ready to live alone or even with anyone else. I’m about to turn 40. I hope I manage to get back on my feet.’

Asmae

ROOM 244

Listen

Asmae

ROOM 244

‘I arrived in Belgium when I was 19. I followed a Belgian- Moroccan man I had met in Tangier, Morocco. I struggled to cope with being away from home, with the lack of sun, the strange food. I was depressed for a long time. Then I got pregnant. Twice. I was having problems with my partner. I got pregnant a third time.

A doctor at the ONE (Birth and Childhood Service) saw my bruises during a consultation and referred me and my two sons to a shelter. When my little girl was born, I moved to another shelter with my three children, before finding a flat in the Lemonnier district of Brussels. But the flat was squalid; there were mice and cockroaches. The CPAS (Public Centre for Social Welfare) put me up in temporary accommodation close to Botanique, but it was impossible to stay there with three children. So, they went to live with their dad.

I accidentally got pregnant again. I was hospitalised and managed to get myself completely clean, until a few weeks before the birth. My baby daughter was put into care.

Nothing heals the wounds from childhood, and mine was very difficult. My mother used to hit me a lot. I was the youngest of seven children. My father worked on the docks in Tangier. In one memory I have of my mother she is holding a knife to my throat to make me stop coughing. Such memories haunt me.

I would really like to get myself back on track – for the sake of my children if nothing else. But I don’t yet feel ready to have them come and live with me in an apartment. I need to take care of myself and fix my problems. That’s the first step.’

Laetitia

ROOM 203

Listen

Laetitia

ROOM 203

‘I’ve done some modelling, you know. I know how to strike a pose. I was 18, tall, slim and beautiful. But completely miserable. My stepfather was a pimp and my mother a prostitute. I was exposed to the horrors of that underworld far too young.

Alcohol and drugs (heroin and cocaine) helped me cope. I’ve quit the drugs; I’m on methadone. Alcohol is a harder habit to kick.

I had met a super violent man. He bust my spleen, broke my nose, pulled out half my hair... I could go on. He was harassing me, pestering me for money. I was so scared.

I’ve been sleeping on the streets for 10 years now. There, I was reunited with my sister after years apart. It’s a real relief to have her by my side. I’ve made some friends too: we talk, help each other out, support each other. This provides some comfort.’

Conchita

ROOM 245

Listen

Conchita

ROOM 245

‘At 18, I fell in love with an Italian and got pregnant. We got married straight away and moved in together. We started working: him as a coach driver and me as a hairdresser. Thirteen years and two sons later, we got divorced. Shortly afterwards, I met another man. He was very violent. One day, he smashed a window and shouted: ‘You can either walk backwards over the broken glass, or walk forwards and I’ll head-butt you!’ I went for the broken glass. He also ran me over with his car. I had three children with him, including twins. While I was pregnant with them, he kicked me in the stomach so hard my waters broke. The final stage of my pregnancy was very difficult. Once the twins were born, their father did a disappearing act. Good riddance!

My children are aged between 19 and 30 years old. They are all well, except the third, who suffers from psychosis. In early 2020, he was at my house when he had an episode. He was taken to hospital and then it was me who started to lose it as I thought he had abandoned me. I stopped paying my rent and got evicted, finding myself on the streets for the first time in my life. I would wander aimlessly around the Gare du Midi and Place Anneessens. It was really tough: the cold, the men making comments like ‘Come and shower at mine,’ and then trying to rape you when you fall for it.

This is not the way my life was supposed to turn out. I was born in Saint-Gilles. My family was from Spain. My mum was a cleaner and my dad a pub landlord. I had a happy childhood, did fine at school. And yet here I am, homeless at 54 years of age.

I lived out the coronavirus crisis in parks and train stations. But, delirious, I didn’t believe the pandemic was real: I thought the whole world had clubbed together to play a trick on me! I was completely paranoid. At a certain point, though, sense got the upper hand and I said to myself: ‘It’s a bit far-fetched to think that so many people might be taking the piss out of me.’ It’s lucky that I came across the Samusocial; I’d have ended it all if it were not for them. It was when I arrived at Square de Meeûs that I started to live again. I was welcomed with respect and kindness. I saw a psychologist and was given medication; my hallucinations have gone, and I no longer feel sad and lonely. They’ve also helped me find an apartment. So, I won’t end up back on the streets.’

In the midst of the global pandemic, we asked ourselves one question: how can a public institution support those who are suffering? How can it make itself useful to the citizens it represents, and above all the most vulnerable? Not by seeking to do charity, but because we believe it is the duty of public institutions to be as close as possible to the weakest in society, to the most vulnerable, to those in the grip of human suffering. For this, among other reasons, we decided to throw open the doors of one of our buildings, the Helmut Kohl building, to homeless women. I wish to thank the Samusocial organisation in Brussels for their longstanding efforts and dedication to help us make this project a reality.

Is it enough? Is it too little? It is, when all is said and done, something that a public institution simply has to do. It must engage in close dialogue with civil society and protect those who are suffering or find themselves shut out from the unfathomable workings of a world that has to be reformed. For this institution, the European Parliament, is also their home. And this is the Europe that many of us want to see: a Europe of solidarity. This series of portraits tells the bright story of a Union that is changing.

David Sassoli, President of the European Parliament

We sometimes forget that behind the statistics there are individuals with a sinuous path and a dented life. The portraits of these women confront us with our fragility in the face of life’s accidents. Above all, these stories remind us that being a woman today is still to suffer domination and violence. These women and their struggling companions have now to rebuild themselves. To do so, the priority is to provide them with a roof to shelter their fights. I am therefore delighted to be associated with this series of portraits, which keeps track of the experience of a constructive collaboration and gives a voice to those concerned. I warmly thank the European Parliament for having opened its building in a context of a health crisis that is hitting homeless people hard. I also thank the New Samusocial for its professionalism, which has allowed many women to be welcomed with dignity and adequately accompanied.

Alain Maron, Brussels Minister of Social Action and Health

The COVID-19 situation has exacerbated the vulnerability of certain groups of people, in particular homeless women, who are amongst the worst-impacted segments of the population.

This exhibition, “Femmes” [“Women”], is a wonderful opportunity to change the way we look at them, to forget their homelessness for a while, to discover or rediscover the women they are, first and foremost. This exhibition is also the result of new mechanisms for solidarity put into place during this crisis: all the women you will “meet” here have been given accommodation in the Helmut Kohl building made available for our use by the European Parliament. By offering them a safe, secure place to stay, exclusively for women, available to them at all hours of the day and night, we quickly saw many of them come back to life! This restored dignity is magnificently emphasised in the portraits by Gaël Turine, and sharing their stories with writer Anne-Cécile Huwart has undoubtedly played an integral part in a lengthy process of rebuilding their lives and reintegrating into society.

Stéphane Heymans, President of Samusocial Brussels

We would like to thank the teams of the Samusocial as well as all the people on the ground for their daily commitment to the most vulnerable.